I am a word nerd. I love to geek out on weird and wonderful applications like Scrivener, Microsoft Word, Grammarly and the Hemingway Editor. These programs are innovative and can do some of the heavy-lifting for writers, especially in commercial writing, social media and journalism, catching spelling mistakes and proofing for small errors.

But for novelists, poets and short story writers, editing programs are like talking to your drunken roommate from college; they don’t always make a lot of sense. Allowing an editing program to decide how you should write is a critical mistake. Writing software has certain weaknesses, just check out the infamous spell check poem which proves conclusively that spellcheck is not the boss of you.

Editing programs cannot detect rhythm or poetic metaphor or choose when the passive voice is more powerful than the active voice. Complex sentence structure baffles the algorithms of these applications. One day maybe, but not now.

Editing and spelling software cannot replace education or instinct. Writers need to learn the rules in order to make conscious choices. But to master rules, you need to know when to break them. Dictates like “never write in the passive voice,” or “don’t use adverbs” or “break up your sentences,” are guides, not absolutes. Subjugating your writing to hard rules can kill the musicality of your prose and destroy innovative expression.

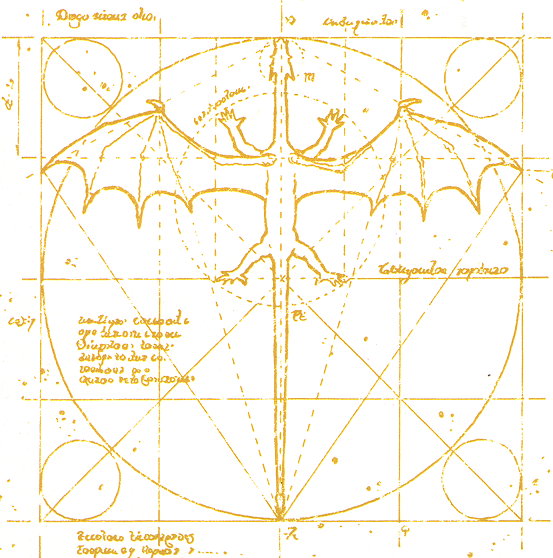

And as you will see, creating software that acts as a definitive, authoritarian template is a slippery process. To illustrate my point, I ran a section of Nobel Prize winning novelist Gabriel García Márquez’s masterpiece One Hundred Years of Solitude, through the Hemingway Editor.

Here is what I got:

As you can see, the program exacted its hard logic, marking long and complex sentences, despairing at the passive voice, wagging its electric finger at adverbs and claiming the passage was hard to read. In this case, following the robotic advice would be disastrous, undermining the beauty and power of the prose.

As you can see, the program exacted its hard logic, marking long and complex sentences, despairing at the passive voice, wagging its electric finger at adverbs and claiming the passage was hard to read. In this case, following the robotic advice would be disastrous, undermining the beauty and power of the prose.

Can your writing ever benefit from using an editing program? Sure, especially when it comes to proofreading. Grammarly has saved my ass more times than I can count. But you can’t let a program do your thinking for you, or you’ll sound like a robot. Writers are like magicians, you need to roll up your sleeves and learn the damned tricks. Writing well is hard work. Nothing will replace study and expanding your awareness.

Instead of trying to force your writing to adhere to an artificial set of rules, next time you read a brillant passage in a book you love, ask yourself —how did the writer pull that off? Why did the passage work? Did the words create suspense or pathos? Why? Once you integrate the knowledge, you’ll know when its time to break the rules.

Even the suggestions from this program give me hives. Stay away from mechanized Business English ‘solutions’ and learn to analyze your own prose. It’s really not that hard – after a number, say, of articles and blog posts on adverbs, plus a look at a genuine guide (I use The Handbook of Good English), and you will have a good idea of where and why to use them.

Using this kind of ‘editor’ keeps you from learning – unless all you use it for, as I do, is to count said adverbs for you – so you can go look for yourself and see if the number and ones you used are what you intended.

Novels aren’t for beginners.

Words to live by, Alicia. I can’t wait to see what happens when I run Moby Dick through this software.